Lambing season is now in full swing, with fields filling bouncy lambs and the sound of cute bleating. There is lots to understand about lambing. For smallholders who are lambing for the first time, to those who want to know more about lambing, this post aims to answer your questions about the preparing, birthing and caring for lambs.

Preparing for Lambing

Although lambs have been born outside for thousands of years, it is much better (and easier!) for you to bring ewes inside to lamb. It helps keep the lambs safe from predators and the elements, plus you can be on hand to help with difficult births if necessary. The lambing shed should be thoroughly cleaned with a disinfectant and have a plentiful layer of fresh straw. Keeping conditions as hygienic as possible will prevent bacteria from building up and reduce the risk of lambs and ewes getting infections. There should be a good supply of hay and water available at all times.

Basic Lambing Kit

Before lambing, having some essential kit ready for use will save you time and stress. When lambs are being born, you don’t want to be fumbling around, trying to remember where you put something. Have everything you need clean and to hand.

Basic Lambing Kit:

- Towels or cloths – for wiping mucus and drying off lambs.

- Iodine solution and cup – for dipping lamb umbilical cord. A 1:1 iodine and surgical spirit mix provides even application.

- Scissors and thread – for cutting and tying umbilical cord, if necessary.

- Halter – useful if you need to secure a ewe.

- Disposable gloves – for examining a ewe and handling afterbirth.

- Lubrication – for applying to gloves before examining ewe, or to apply to a dry lamb to reposition it for birth if necessary.

- Lambing ropes – if you need to assist.

- Warming box, and heat lamps or mats – to warm cold lambs.

- Medications – antibiotics and painkillers might be needed to treat a ewe that needs assistance. Glucose might be needed for a weak lamb. Discuss this with a vet before lambing.

- Twin lamb drench for weaker ewes, some injectable calcium.

- Supply of sheep colostrum, syringes, feeding bottles and teats – to feed or care for lambs unable to nurse.

- Thermometer – to check temperature of cold lambs.

- Bucket, water, mild soap – for washing hands, and the ewe if necessary.

Sheep Labour and Lambing

A few days before ewes are due to lamb, their udders will begin to swell, as will the vulva. The first stage of labour has started when you notice the ewe pawing the straw, or being restless. This can last for a few hours. Eventually, as the contractions get stronger and more frequent, the ewe will lay on her side. A thick mucus comes from the vulva before the appearance of a lamb.

Lambs are usually born with forelegs first, together with their nose and head. Often they are still in the membrane. The ewe will continue to push the lamb out, and this can take a few minutes.

Once the lamb is born, the umbilical cord should break naturally. If it does not, encourage it to break by moving the lamb away from the ewe. Mucus and membranes should be wiped from the mouth and nose, so it is easier for the lamb to breathe. Dip the end of the umbilical cord with a prepared iodine solution to help dry it out and prevent bacteria from wicking along it, which can cause illness.

The ewe should show interest in her lamb by licking it, and bonding with it. This is a good time to gently check her udders to see that milk is available. Sometimes there is a waxy plug in the teat, and squeezing it out makes it easier for the lamb to get on with having its first colostrum milk.

If the ewe has twins or triplets, the next lambs could arrive within minutes or could be half an hour between them. Once the first has been born, move it to a side pen that has a good layer of fresh bedding, and the ewe will follow. Separating them from the flock allows them to bond, and stops the ewes that have yet to lamb from showing too much enthusiastic interest.

When to Intervene when Lambing

If a ewe is taking a long time, or appears to be struggling to lamb, you might need to help. You will also need to assist if just the lamb’s head appears without its hooves, or if just a leg or tail is visible.

It’s always a good idea to have someone experienced with you if you have never lambed before, so you can learn how to examine the ewe and decide what to do. You might need to gently put your arm inside to feel the position of the lamb. Hygiene is important to prevent infections, so wash your skin thoroughly or use long surgical gloves. You should also lubricate.

Lambs that are not in the right position to be born can be gently pushed back towards the uterus and positioned more favourably. Depending on the position, a lambing rope might be used to help apply pressure, or to help keep track on what legs are where. Again, get an experienced person to teach you how to use lambing ropes before attempting it yourself.

Sometimes a large lamb might need some encouragement to come out. Feel with your hands and gently pull each foreleg to ensure they are straight. Grip the feet with one hand and use your other hand to feel the back of the lamb’s head. Pull slowly with a slight downward motion to encourage the lamb to come out. Once the head and shoulders are out, the rest of the lamb should naturally follow.

When you have to intervene, having some practical experience will give you confidence. A good lambing course really is helpful, and gives you a base of skills to use.

The Newborn Lamb

It is vital that a newborn lamb gets some colostrum from the ewe’s milk within two hours of being born. This creamy first milk contains antibodies that help protect the lamb from infections and disease, and it has just the right nutrients it needs to give it energy for life.

If suckling is not going well, the lamb will become hungry and from there things can take a turn for the worse rather quickly. A hungry lamb has a hunched appearance, and you should provide it with replacement colostrum, either milked from a ewe, or from your lambing kit, using a feeding bottle or syringe. Colostrum from goats or cows can also be used, provided those animals are free from disease. An average sized lamb that weighs around 4kg requires 200ml to be fed four or five times during the first 24 hours.

All effort should be made to get the lamb to drink from the ewe, as bottle feeding lambs is inconvenient and time consuming. If the lamb is not getting milk from the ewe, you need to find out why. Check the udders for signs of heat or swelling, as this could be a symptom of mastitis, a bacterial infection, and need treatment with antibiotics. Lambs can sometimes be sucking of a piece of long fleece, rather than a teat, so clip the fleece short to make them easier for the lamb to find.

After lambing, give the ewe some fresh water and quality hay. Giving warm water is recommended and some liquid molasses in it will encourage her to rehydrate and also give her a bit of energy. The afterbirth should follow, taking no longer than eight hours to pass. The ewe is likely to eat it, but if you find it before them it’s a good idea to remove it to keep the area hygienic.

Leave the ewes and lambs in the side pen for a day or so and keep an eye on them to make sure lambs are getting enough milk. Once you are happy that lambs are nursing well, the ewe is in good health and a strong bond has developed, they can be turned out into field.

Lambs should be ear tagged in the weeks after they are born, but waiting for a couple of months until their ears have grown is beneficial.

Warming Cold Lambs

If a lamb does not get enough colostrum, it can get hypothermia which causes a lamb to deteriorate quickly. Lambs have enough brown fat to keep them going for the first few hours of life, but if they do not get the nutrients from colostrum, that fat begins to be used for energy and the lamb struggles to regulate its temperature.

Symptoms of a cold lamb is a lethargy and a reluctance to stand. If you think a lamb might be cold, a quick way to check is to put your finger in its mouth. If it feels cold inside, the lamb is also cold. It is useful to get an accurate measurement using the thermometer. The Normal temperature for a lamb is 39 to 40°C.

TIP! A lamb warming box is an effective way to warm cold lambs. It can easily be made using plywood, with a mesh or wooden slatted floor to allow heated air to flow from underneath so it circulates around the lamb. A fan heater on a warm setting works well for this, but make sure the edge of the heater is not too close. Warm the lamb until its temperature reaches 38°C. Put a thermometer in the box to keep an eye on the temperature inside to make sure the lamb doesn’t overheat.

For a mildly hypothermic lamb with a temperature higher than 37°C, move it to a warm place and feed some colostrum.

If you have a seriously hypothermic lamb, you will need to take action to warm it up and get some colostrum in. How you do it depends on the age and condition of the lamb.

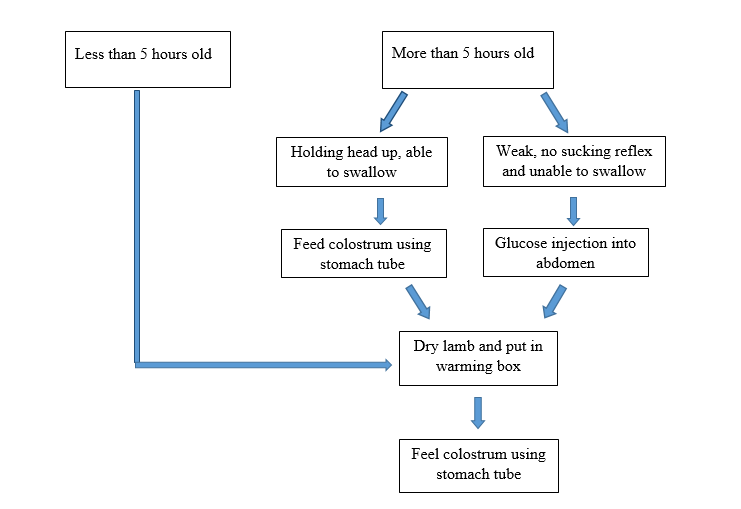

One rule of thumb is that if the lamb is less than five hours old, it will need warming before feeding colostrum via a tube. For lambs that are more than five hours old, the condition can be more serious because even more of its brown fat reserves will have been depleted. It needs energy before being warmed, as warming a chilled lamb speeds up its metabolism and uses even more of its fat reserves. Depending on the condition of the lamb, it will need colostrum or require a glucose injection close to the navel, before being warmed and fed. A vet will be happy to show you how to do this prior to lambing, and will also show you how to correctly insert a stomach tube.

The chart below shows the course of action for treating hypothermic lambs with a temperature of 37°C or below.

Once you are happy that the lamb is warm and has a good sucking reflex, it can be returned to the ewe and monitored. If the lamb is still weak, it will need to be kept in a warm, draught free area and tube fed until it is stronger.

Once you are happy that the lamb is warm and has a good sucking reflex, it can be returned to the ewe and monitored. If the lamb is still weak, it will need to be kept in a warm, draught free area and tube fed until it is stronger.

This article is an excerpt from the sheep chapter of my book Smallholding – A Beginner’s Guide to Raising Livestock and Growing Garden Produce. Other livestock care includes cattle, goats, pigs, llamas and alpacas.

Please share your lambing experiences, or if you are just starting out, what do you want to know most about lambing? Please comment!